Editor’s Note: Last weekend we published the first installment of Lay Me Down here on Mountain Passages. If you haven’t read it, check it out at https://alanstark1.substack.com/p/lay-me-down It’s a fine piece of writing.

John and I go back to the beginning of the century when I was working as the associate publisher of Mountain Sport Press and John was the publisher/editor of Mountain Gazette. We put a book together called When in Doubt Go Higher, that was my idea in spite of what John says, and have stayed in touch over the years.

We can be a little hard on one another, so here is his bio from his latest book without one single blatantly gratuitous comment from me.

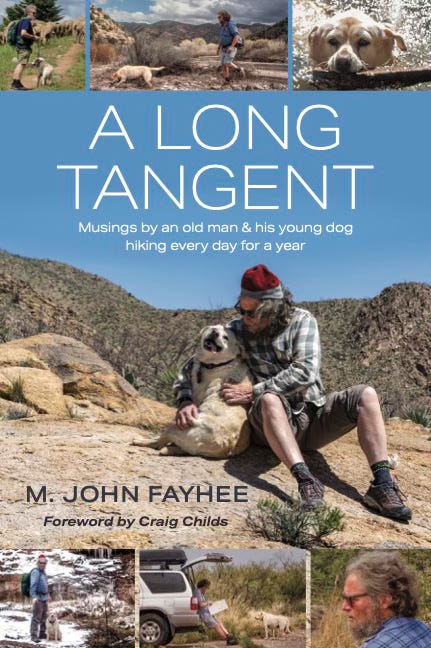

M. John Fayhee’s most recent book, “A Long Tangent: Musings by an Old Man & His Young Dog Hiking Every Day for a Year” (Mimbres Press) was a 2024 New Mexico-Arizona Book Award winner.

For twelve years, Fayhee was the editor of the Mountain Gazette. He was a longtime contributing editor at Backpacker magazine. A two-time Colorado Book Awards finalist, his work has appeared in Canoe & Kayak, the High Country News, REI Co-Op Journal, Overland Journal, Islands, Adventure Travel, Men’s Fitness, New Mexico Magazine and many others.

Fayhee has hiked on five continents and has completed the Appalachian, Colorado, Arizona, and Inca trails, as well as the Colorado section of the Continental Divide Trail. Last summer he completed the 100-mile GR20 in Corsica, purported to be the most difficult trail in Europe.

Fayhee is, improbably enough, a New Mexico Humanities Council Scholar.

He lives in New Mexico’s Gila Country with his wife, Gay Gangel-Fayhee.

So here we go with the final installment.

In the first installment our hero had acquired a much used and abused mattress that he described as, “There were unidentifiable discolorations mixed with mysterious blotches interspersed with inexplicable smudges commingling with bewildering blemishes. Basically, it looked like a biker-gang-related crime scene that had transpired in a Third World meatpacking plant. It’s fair to say the DNA was highly contaminated.”

He also introduced us to his friend Willie and described a bacchanal gone way over the edge, ending in a visit to the ER.

Phase Three: Paradoxical

That nasty mattress stayed with me for several years. It alternated between the floor of the various slums I called home and the back of my battered van. It was while taking refuge in that van that it absorbed additional stains.

There was a post-midterm Bacchanal scheduled for the Middle Box of the Gila River, just downriver from where I extricated Willie from his seizure nightmare. I drove to the correct coordinates and spent an appropriate number of hours engaging in academic discourse with people whose tongues were lolling out of their mouths. Somewhere between dusk and dawn, I decided it was time to part ways with my fellow revelers, most of whom, like me, were too hammered to articulate proper valedictions.

One person who was face-planted in the sand bordering the river was an amigo I’ll call Hawk, who was, even by New Mexico’s forgiving cultural barometer, a strange hombre. He was, first of all, 20 years the senior of most every student at our local college. He had opted to return to the classroom with a grey beard and arthritic hands bent into perpetual claws partially because he was tired of living a bottom-feeder hippie lifestyle and partially because he, a Vietnam veteran, qualified for generous financial aid. And, because he had a young son, he was also given a subsidized on-campus apartment, which he shared with an extended tribe of fellow Rainbow Family members, most of whom were named Moonbeam, Cinnamon and Dancing Bear.

Hawk was a talented and passionate writer who I employed to work for me at the student newspaper, which I edited for three years. We became friends, though I have to admit his omnipresent philosophical eccentricity often negatively impacted my attempts to seduce some of the coeds who then traveled on the periphery of my social trapezoid.

Hawk maintained a working still in the back of his apartment. The still was actually owned and operated by a crusty old hard-rock miner I’ll call Cactus Jack. Cactus Jack, who passed away several weeks after being thrown from a highway overpass by someone who was never identified, much less brought to justice, was an in-your-face barroom evangelist who downed boilermakers at the Drifter Lounge in between rambling tabletop invocations. He also taught me how to pan for gold, a skill I managed over the years to parlay into numerous paid writing assignments, including the first piece I ever sold to Backpacker magazine, where I ended up working as a contributing editor for more than a decade.

Hawk drank Cactus Jack’s homemade moonshine like he was trying to drown something dark. This often resulted in a loss of not only coherency but also consciousness. Which was clearly the case as the post-midterm gathering at the Middle Box was embering its way toward dissipation. Though I suspected I would later grow to regret it, I dragged Hawk back to my van by one leg and leveraged his dazed carcass onto the mattress. I tried to impart some salient information — stuff like who I was and where I was taking him — but all he could do was snore, drool and yak, adding extra layers of DNA to my already-repulsive rack.

Halfway home, I had to stop to take a leak. I pulled over near Saddle Rock Road, exited the van and relieved myself. As I was doing so, I shouted back, asking Hawk if he was OK. I heard a groan that sounded more or less affirmative in nature, which, in my mind, meant he was still alive, if not exactly kicking.

Twenty miles later, I parked in front of his apartment and walked around to help my sloshed chum inside, only to observe that, where I expected Hawk to be, he was not. This was more of a concern than it might have been in ordinary circumstances, since my van did not have any doors. There was no driver-side door. There was no passenger-side door. Where there were normally two side doors, there were no doors. Where there once had been two back doors, there were no doors. I had removed all six doors because they, being rusted through and ready to fall off anyhow, rattled loudly and that noise bothered me. While a lack of doors did not exactly improve the overall safety coefficient of the vehicle, it sufficiently addressed the noise issue while simultaneously providing a 360-degree vista.

Admittedly, I was not thinking all that clearly, but, still, I was able to mentally muster a plausible explanation regarding my missing muchacho: He had obviously fallen out of my van somewhere between Saddle Rock Road and where I now stood bumfuzzled. There was of course only one option: I had to drive back to initiate a salvage run for whatever might be left of Hawk.

But there was a not-inconsequential problem: The gas gauge on my old van was pointed down toward the center of the Earth — a common state of affairs. At that time of night back in those pre-24-hour-C-store days, there was nary a station open, which did not matter, since, as usual, I was near-bouts penniless.

There was but one plausible course of action: I drove up a side street to the residence of the man who had gifted me a stolen IBM Selectric typewriter — the same man who had joined us on our doomed foray to Turkey Creek Hot Springs. I parked several houses away and pulled from the back of my van my primitive gas-siphoning kit — consisting of a five-foot section of cut-off garden hose. a two-gallon plastic bucket and a funnel — which I kept on board in case such emergencies arose, which they often did. I tiptoed to the typewriter thief’s truck, inserted one end on the hose into his unlocked gas tank, sucked on the other end till I coaxed a flow and filled the bucket to brimming. Usually, when stealing other people’s gas, I took only as much as I might need to get home, since I liked to think I had some scruples buried somewhere beneath my larcenous exterior. This time, though, I made several trips and pretty much emptied the typewriter thief’s tank.

Payback.

I then headed west on U.S. Highway 180, entertaining while I did so the myriad potential negative possibilities I was facing.

First, there was a good chance I would not locate Hawk, at least until daybreak. If he had indeed rolled out the back of the van, he likely had careened off the road into the brush.

Still, it was possible he had thudded down in the middle of the blacktop, upon which case he would likely have been run over, maybe several times. While the thought of Hawk lying on the center stripe with tire tracks across his chest made me wince, those thoughts eventually wandered to potential interfaces with the judicial system. What was my culpability? Was I to blame for whatever harm might have befallen my buddy, inadvertent as my actions might have been?

What if I rounded a bend and there was an ambulance and a gaggle of sheriff’s cars, lights a-blazing, while a team of paramedics attempted to revive a moonshine-breathed man whose last words were “John Fayhee.” I myself was inebriated. My driver’s license was both long lost and long expired. I had no insurance. Because I had acquired my van under extra-legal circumstances, I had no vehicle registration.

I could be in deep trouble.

This indeed presented an ethical conundrum.

I mean, I liked Hawk just fine, but not enough to go to prison for him, especially if he was already expired.

By the time all these thoughts were bouncing around in my head like pinballs on speed, I rounded a bend and there on the shoulder was Hawk, upright, but staggering badly, headed in exactly the wrong direction. I pulled over and asked if he wanted a ride.

“Why did you leave me?” he slurred pitifully.

“I figured you needed the exercise,” I responded with faux nonchalance camouflaging a degree of relief that almost had me in tears. It was all I could do to refrain from hugging Hawk there on the side of the highway, except his BO would have knocked a buzzard off a shit wagon.

Ended up that, when I yelled after his well being while I was urinating, he attained something approximating functional consciousness, and, as I was returning to my position as pilot of my pitiful excuse for transportation, he simultaneously got out to relieve himself. He said he was quite startled to see me drive off.

“I was pissing as fast as I could!” he exclaimed. “You should be more patient!”

True, that.

I helped him back on the mattress and took him home without further mishap.

That mattress and I parted ways when I abandoned a primitive camp way out in the desert. The mattress had been placed on the ground next to a big juniper, where I slept night after night under the stars with a dog and a cat — who added to the stain milieu by bearing four kittens upon it. When monsoon season hit full force, I was backpacking in the Gila Wilderness and the mattress got soaked beyond salvation. I left it beneath the tree, where its remnants might still lie.

As for the van, which by then hardly ran: When I moved to Colorado in 1982, I handed the keys to a man I hardly knew. I took a bus north, to begin life anew in a place where climatic reality required that all vehicles sport doors.

Phase Four: Rapid Eye Movement

Last week, with mattress-based thoughts swirling in my head, I decided to try to hunt that old shack down, the homey little place from which, with Willie’s directions, I had liberated the funky mattress upon which Hawk once rested, until I accidentally left him standing on the side of a dark highway, holding his johnson. The dirt road now has a formal, though prosaic, name: Radio Tower Road — which, not surprisingly, accesses the summit of two peaks that are thick with various species of antennae, dishes, discs and, in all likelihood, electronic surveillance apparatus owned and operated by Homeland Security, which maintains a noticeable, some would say obtrusive, un-Constitutional presence in the borderland area.

When I sought that well-used mattress all those years ago, few people traveled up this road. The mining operations, the remnants of which are visible from the highway connecting Silver City with Pinos Altos, had long been abandoned and, in those delightfully primitive days, the peaks were clear of electronics. Thus, there was no reason to maintain the road. Few people drove up there. Now, with the texting needs of thousands of people depending upon the upkeep of those antennae, dishes and discs, Radio Tower Road is frequently graded and therefore is smooth enough to accommodate passenger vehicles.

I parked at the bottom and, with my dog, set out on foot, opting to combine a stroll down memory lane with some exercise.

With rain clouds forming thickly overhead, we took off toward the summit of the mountain with the most antennae. The road contoured along the edge of the ridge, passing into and out of numerous side drainages.

Ahead, in the middle of some of the various mine-tailing piles, I visually acquired my target. Because of the serpentine nature of the road, it took a half-hour to get there, and, when I did, the shack was nowhere to be seen. It was either hidden by trees, or perhaps I had seen something that, from a distance, was a mirage. I continued on toward the summit, but was stopped cold with a no-nonsense “No Trespassing” sign and a locked gate.

On the way back down, I walked more slowly, examining the lay of the land, which was dominated by trash — the bane of rural New Mexico. There was plenty of simple litter: fast-food packaging, beer and soda cans and broken glass. There were uncountable spent shell casings, as this, like many areas in the sunny Southwest, is utilized with enthusiasm by people opting to bear arms without opting to clean up after themselves.

There was also a stunning amount of household refuse dumped off the side of the road. Entire truckloads of discarded appliances and furniture filled otherwise scenic side canyons. Intertwined in that refuse were several mattresses. I stood there, raindrops pattering off my hat, wondering about the stories those mattresses might tell. Few household items can trump mattresses for narrative resonance. Dreams. Lovemaking. Going to bed mad. Illness. Scared toddlers looking for parental comfort. Abandonment. Disconsolation. Fretfulness. Prayer. Death.

All reduced to garbage.

I exited the road and entered into one of the dead zones defined by deserted mining operations. While there is much to admire about the place such enterprises hold in the mythology of the Wild West — ingenuity, toughness, vision — the truth of the matter is that most long disused mine sites are ecological disasters with half-lives measured in centuries. I always tiptoe across their toxic soil with trepidation, as though the host of poisons contained therein might seep through the soles of my boots like radioactive Ebola. I breathe less deeply. I wince when viewing the unnatural coloration that defines the polluted pallet of abandoned mines.

Right in the middle of a sea of crumbled cinder was the shack. It had seen some hard times since my last visit decades ago. One side was riddled with pockmarks left by point-blank weapons discharge. It looked like the wall of a firing squad facility. There was no colorful Navajo blanket covering the door. No candles. No table and chair. No calendars. The inside was a disgusting muddy mess, with what I guessed to be uninspired occult designs on the walls. Dark sullen dankness defined the ambiance. The thought that this place was once used as a domicile, even by people with nowhere else to hang their hat, was impossible to fathom. The thought that I once pilfered a mattress from these dreary confines made my skin crawl at the same time it made me smile.

Like many people knocking with gnarled fists upon the door of their sixth decade, I find myself wistfully mentally wandering back to days when I did not have more parts that hurt than parts that do not hurt. When my back was straight and fully able to solo wrestle a saturated and befouled mattress from a shack into the back of a doorless van. When I crashed on whatever came between me and the cold, hard ground.

Phase Five: Awakening

Concurrent with the decision to buy a new mattress is the question of what we will do with the mattress that now serves as the setting for my slumber. I have spent more time directly connected to that mattress than I have any other piece of furniture I own. Certainly, it does not have the historic cachet of my desk, which was once owned by a famous personality. It does not have the coolness of our oak dining room table or our Victorian couch.

Still — upon that mattress, I have pulled the covers around my chin on many a rainy morning. I have taken multitudinous afternoon naps. I have played hand-under-the-blanket with our purring cat for hours on end. Upon its folds, I have dreamed of crossing mountain ridges that defied the laws of gravity. I have dreamed of sailing to Greenland through cold seas with waves as high as the moon. Upon its folds, I have lied awake at 3 a.m. attempting to fabricate a suitable denouement for a nearly finished essay. I have tossed and turned over missed deadlines. I have passed out drunk upon its glorious ridges and folds more times than I care to count. Upon it I writhed for almost three weeks when infected with the H1N1 flu virus. It is upon that mattress that my wife and I consoled each other the night we had to put our old dog down. And it was upon that mattress that I lay prostrate for a week, knocked woozy by painkillers, when I hurt my back three days before we were scheduled to leave on a trip to Cuba.

With all mattresses, there is yin and there is yang. Most of us come in on a mattress and most of us will go out on one, too.

I suspect we will take that mattress to the Habitat for Humanity Re-Store on the other side of town. We recycle the detritus of our almost embarrassingly middle-class life there fairly frequently. Last time, it was two badly outdated light fixtures placed in our house by the people who built it during the Summer of Love. Before I even passed onto the Re-Store property, a woman probably 70 years old who pulled up behind me effused about how lovely those butt-ugly fixtures were. She offered me $5 on the spot. I told her she was welcome to them and she acted the same way I did when I scored that mattress from the shack that is now pockmarked with bullet holes.

One person’s trash is indeed another person’s treasure.

The mattress we will soon discard will make a good bed for someone. I hope it will see long-remembered bedtime stories and giggly slumber parties and passionate lovemaking. I hope it will provide comfort when the flu visits and on the day when the old dog is sent over the rainbow bridge. I hope it becomes a snug bastion in an unpredictable world, a world where sometimes you get a surprise invite to join three buxom lasses on a trip to a beautiful hot spring and sometimes you get left on the side of a lonesome highway while taking a piss under the deep dark New Mexico sky.

END

Order John’s book from your local independent bookseller or any of the usual suspects, M. John Fayhee, A Long Tangent: Musings By an Old Man & His Young Dog Hiking Every Day for a Year, (Mimbres Press), ISBN 978-1-958870-08-2, paperback. It’s a good read. Buy it. Keep John in beer money.

If you would like to comment on John’s essay or just say Hi, send a note to alanbearstark@gmail.com, and I'll pass it along.

Mountain Passages doesn’t pay writers very well, but if you subscribe, I’ll share half the money with John. However a FREE subscription to Substack is available if you just click the button. When you get to the subscription page, go all the way to the right to sign-up for a free subscription. A paid subscription is always appreciated.

If you don’t like subscriptions but like this piece, buy me a cup of coffee by clicking the button below. John will get half, so splurge and buy two cups of coffee.

Don’t like commerce? Times are tough, so I get it. But if you would like to help out, ask a friend to subscribe. In any event, thank you for reading Mountain Passages, an archive is available at alanstark1@substack.com.