If you want to improve your writing, try this. Once a year reread, and consider what Strunk & White dictate about good, clear writing in their famous little book, The Elements of Style. Try not to move your lips as you read.

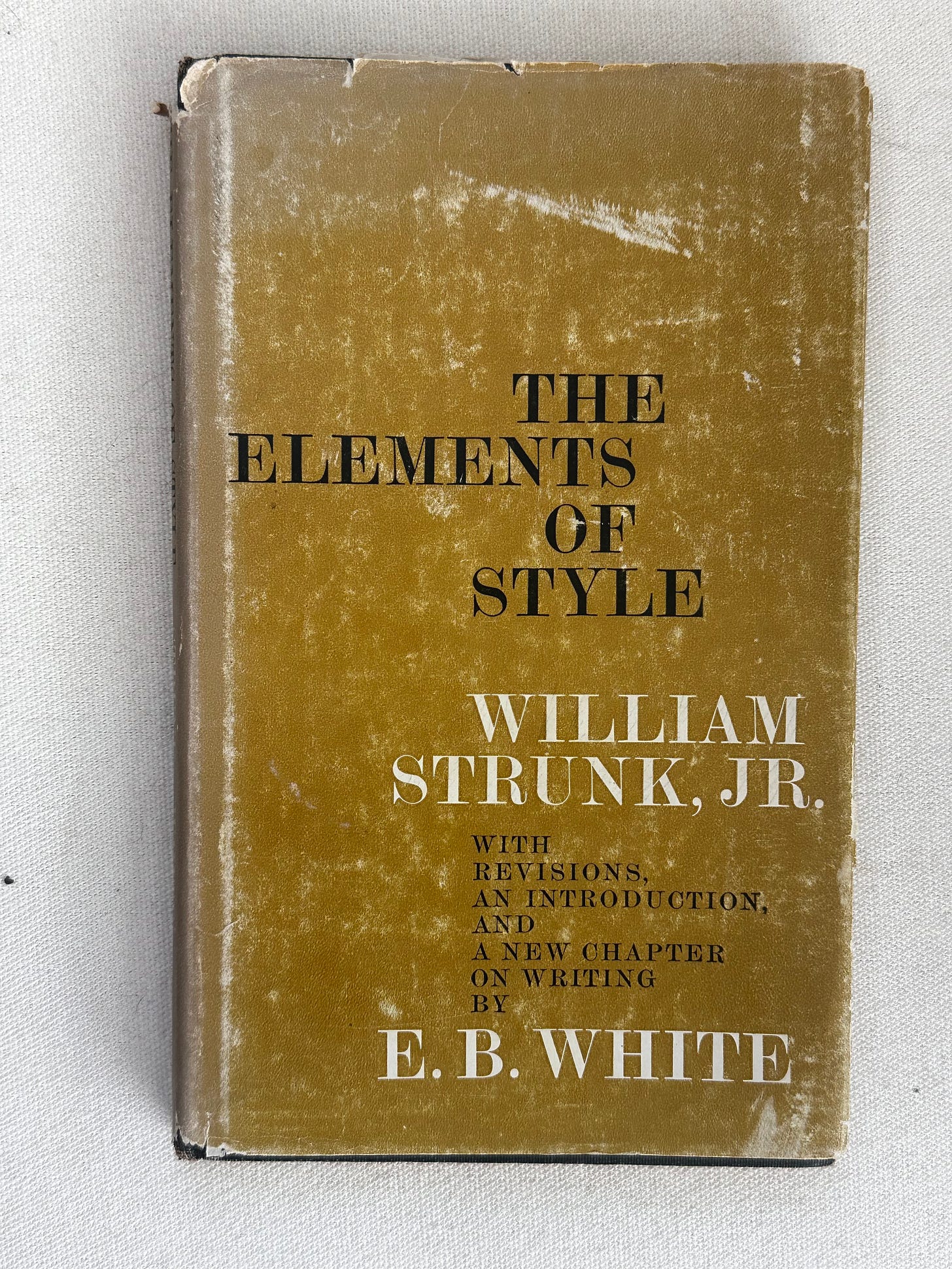

Sitting on the desk beside the laptop is a ratty, underlined copy from the 1959 edition of The Elements of Style that E.B. White revised. I bought it from a used bookseller in St. Paul some years ago when I should have been on campus selling textbooks to professors (a story for another time).

Thumbing through the little book, rereading sections, I am reminded of the sloppiness of my writing and how much I need to simplify my work. But the book also makes me slightly defensive. This is the way I write. I write as if I were talking to you. It is a style that has evolved and I’m sticking with it, as if we were chatting in a coffee shop.

Nonetheless, a reread of Strunk & White helps me, the way a good editor makes an essay better without screwing up the style and message—much. The chapters on usage, composition, and form are all worth reading. However, I am always drawn to the fifth chapter called “An Approach To Style”, which was new material added to the book by White. He says in his front-matter to the book, “The chapter is particularly addressed to those who feel that English prose composition is not only a necessary skill, but a sensible pursuit as well—a way to spend one’s days.”

That is the way I want to spend my days going forward.

However, as I read and consider the 21 rules in this chapter by White, I am overtaken by questions that come to mind, thoughts I want to add to the rules, and gratuitous comments that magically appear on my screen.

Place yourself in the background.

What happened to essay writing rule number two? (2) Write about what you know about. If you were wondering about essay writing rule number one: (1) Keep your day job.

Write in a way that comes naturally.

That would be using a large pencil on cheap paper with big lines and getting my letters legible without my tongue sticking out of the side of my mouth.

Work from a suitable design.

Remember the four types of essays from English 101? Just in case you have forgotten; narrative, descriptive, expository, and argumentative. What horsepucky. When working on an essay just remember Ralph’s, “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”

Write with nouns and verbs.

Try writing without them. I know. I know. This is being disrespectful but White hates adverbs and adjectives because they require you to excise extraneous words, eschew overwriting, and/or avoid classic syntactic mistakes and possibly, just possibly, burnish your golden prose.

Revise and rewrite.

So far I have mostly ignored these rules, but this is good advice, maybe even the best advice from S&W. Revise and rewrite, and then put an essay away for a while, and then revise and rewrite again and again until you get the essay to a point where it is worth sharing. Do not revise and rewrite an essay to oblivion.

6. Do not overwrite.

Ruthlessly cut every other word, well almost—however, some words just have to stay in the essay to prove that, at least, you have a land grant education or a vocabulary that exceeds the number of English majors working as greeters at Walmart, or perhaps, because you just want those words in the essay.

Do not overstate.

An absolutely fantastic, insightful, and concise piece of salient advice.

Avoid the use of qualifiers.

Rather very little information here that can’t be pretty much ignored as another unwarranted attack on adverbs.

Do not affect a breezy manner.

Some sarcastic English professor wrote a truly didactic little textbook subsequently revised by an essayist looking for something to do other than shovel out his barn. The newest edition has been under-revised and over-written by a mixed-metaphor-prone and, as usual, anonymous and lonely editor.

10. Use orthodox spelling.

Geesus!

Do not explain too much.

Prescient advice ignored by every MFA writing instructor in North America.

Do not construct awkward adverbs.

Adverb abuse is not a writerly attribute.

Make sure the reader knows who is speaking.

“Of course, when we read Strunk & White, you should avoid drooling on the more difficult passages,” he said.

Avoid fancy words.

Indubitably.

15. Do not use dialect unless your ear is good.

Y’all get it that we gotta have good ears to be able to write good?

16. Be clear.

Hopefully, in the last analysis, and/or the foreseeable future, clear prose along these lines, is the thrust of this unique text. Or not.

Do not inject opinion.

See #5.

Use figures of speech sparingly.

Fat chance.

Do not take shortcuts at the cost of clarity.

RU kidding me?

Avoid foreign languages.

Por supuesto

Prefer the standard to the offbeat.

BTW b4 U cre8 an essay B familiar with the conventions of the language.

Please.

END (thankfully)

“There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” This quote is attributed to Ernest Hemingway. But sometimes an essay, like this one, just rolls from your fingertips on the keyboard. The hope is that it entertains and reminds you of good ideas about writing that you may have forgotten.

Just getting an essay written, edited, and posted is reward enough. But comments from readers —good, bad or ugly—are also important because a comment says a reader loved, liked, disapproved of, or hated what was written enough to take the time to respond.

For business reasons I suppose, Substack allows only paid subscribers to comment here. So if you are a free subscriber send me a note at alanbearstark@gmail.com. Paid subscribers use the button below please.

If you would like to support Mountain Passages take the time to sign up for a FREE subscription. When the subscription page comes up, just search for the FREE option. Paid subscriptions make my day.

You can also send an essay to a friend or post it on social media by clicking the half square button with the up arrow.

I’m alanstark1@substack.com. Thank you for reading Mountain Passages.

"What's wrong with adverbs?" said Wallace to Gromit, who said nothing at all.

Good to hear opposition to the grammatical rules I have routinely violated.