Author’s Note: This is a chapter from a book-length work-in-progress tentatively titled “Possessed,” which is essentially an autobiography formatted around a series of possessions — a walking stick, some wind chimes, a desk, a bookmark, a world atlas — that have come to define me.

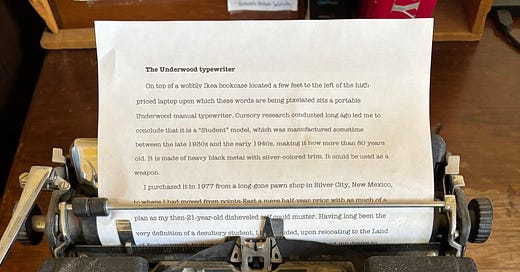

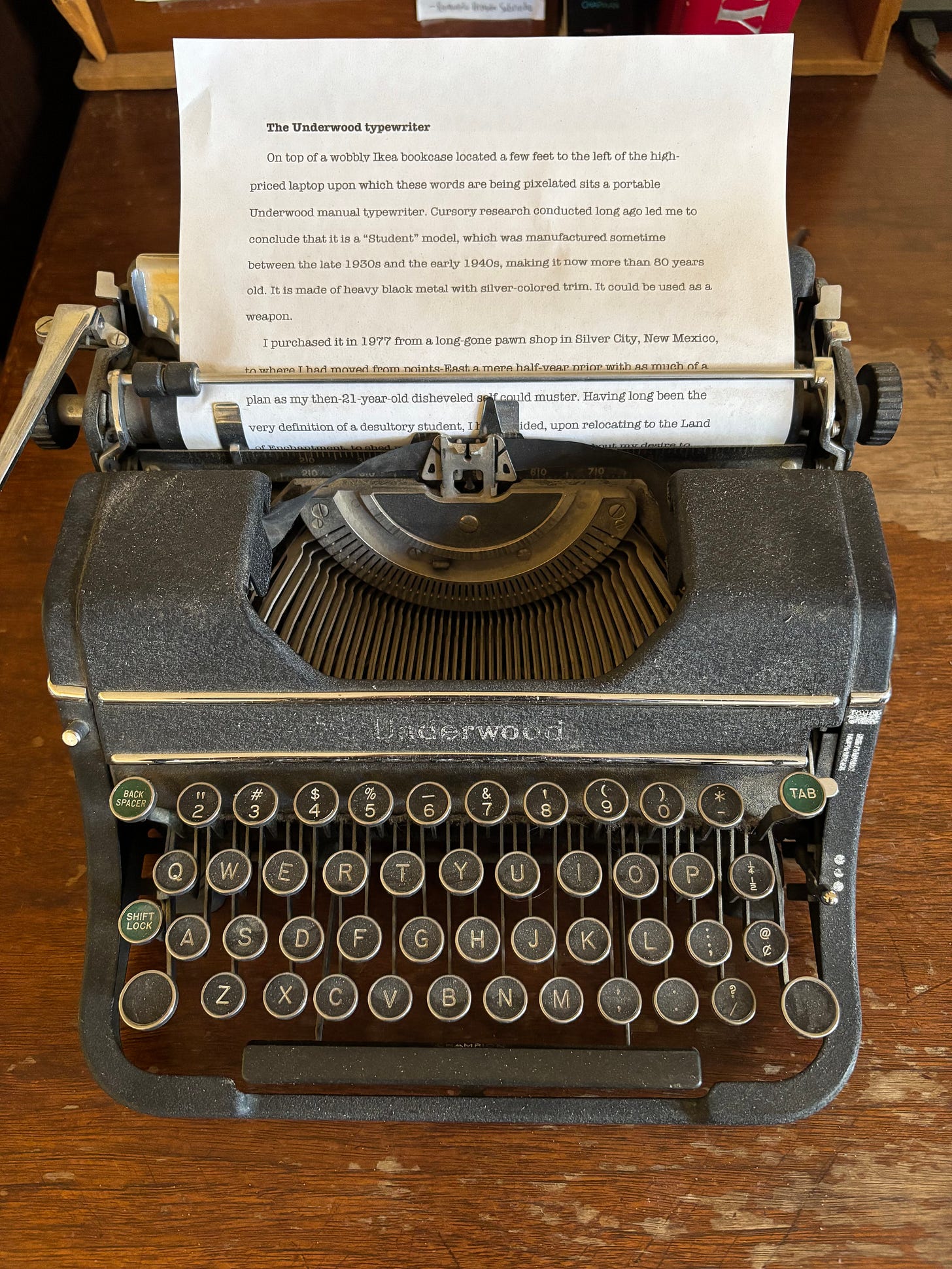

On top of a wobbly, aesthetically unappealing Ikea bookcase located a few feet to the left of the high-priced laptop upon which these words are being pixelated sits a portable Underwood manual typewriter. Cursory research conducted long ago led me to conclude that it is a “Student” model, which was manufactured sometime between the late 1930s and the early 1940s, meaning it is now more than 80 years old. It is made of heavy black metal with silver-colored trim. It has heft. In the right hands and with proper motivation, it could be used as a weapon.

I purchased it in 1977 from a long-gone pawn shop in Silver City, New Mexico, to where I had moved from points East a mere half-year prior with as much of a plan as my then-20-year-old disheveled self could muster. Having long been the very definition of a desultory student, I had decided, upon relocating to the Land of Enchantment, to shed my skin and become semi-serious about my desire to evolve from a borderline illiterate to a partially educated, rent-paying wordsmith. To achieve that end, I would need my very own mechanical means of pouring blood, sweat and tears onto an otherwise innocent blank white page.

Sadly, I knew squat about typewriters. So I enlisted the consulting services of one of my two roommates — who I shall refer to only as “H” — who reluctantly agreed to walk with me — neither of us owning a vehicle — to the pawnshop to lend his expert advice. His single qualification consisted of actually owning a typewriter, though it did not even slightly resemble the machine I was eyeballing, his being relatively new and constructed of flimsy blue plastic. Other than that, H was pretty much a spasmodic klutz who, while able to churn out a well-conceived multi-act play in less than a day, could scarcely tie his own shoes without falling flat on his face.

The pawnshop owner — who asked if I wouldn’t rather spend my money on a gun, of which he boasted an impressive inventory — desultorily pulled the already aged, dust-encrusted Underwood — the only typewriter he had in stock — out and H, after going through a perfunctory examination that amounted to kicking the tires, said it looked fine. I handed over two 20s — likely all the money I had in the world — and toted my weighty acquisition home in its faux leather carrying case.

I placed it upon a desk I had heisted from a previous hovel, sat down and stared at what amounted to a $40 investment in my future (which is about what my future was worth). I tinkered with the various levers, switches and buttons, moved the carriage back and forth a few times and toyed with the ribbon reverse and the touch selector.

Only then did I dare guide a sheet of onion skin (only the best for me!) past the plate, beneath the platen and up through the fingers and type guide. Took me about 12 tries to get it mostly straight.

I sat for many long minutes pondering an appropriate course of action, of which there was only one alternative: I tentatively placed my fingers upon keys that, with the right impact, could unlock the countless possibilities presented by the QWERTY universe.

Then: nothing, because, well …

… I did not know how to type.

This was still in the days when typewriter-deficient students could submit handwritten papers and reports to teachers and professors, which, archaic and inefficient though it may seem now, was cool in its own analog way. Made people pay attention to their penmanship. (A lamentable lost art.) Those days, however, were fading as fast as the eyesight and patience of those laudably accommodating teachers and professors.

My senior year of high school, I enrolled in a typing class. I dis-enrolled within a week. It was scheduled for first period and I had trouble reconciling early morning activities with a life defined by a near-psychotic level of insomnia caused by a violently dysfunctional domestic situation that inspired me to sleep with one eye open. The incessant tap-tap-tapping drove my already jumpy self toward an uncomfortable degree of edginess.

All of which was neither here nor there because I also …

… did not know how to write.

I had provided material for school newspapers since seventh grade and had dabbled halfheartedly in the realms of short stories, poetry and plays. Despite that, I had never paid much attention to such rudimentary literary devices as “beginning,” “middle,” “end” and “making sense.” What I did have going for me was “voice,” which came naturally. But it took a mighty long time to reconcile that one innate positive trait with the undeniable reality that I did not know what the fuck I was doing otherwise.

These things take time. (These things also never end.)

I eventually raised two extended index fingers above the keyboard of my newly procured Underwood, took a deep breath and began pounding away. There were inaccuracies aplenty. Despite my often unfocused efforts, over the next few years, I typed and typed, keeping the manufacturers of Wite-Out and Liquid Paper in business in the process. Annoyed neighbors began referring to me as “the typist.” I am certain my Underwood winced with every errant keystroke.

I have little recollection of that which I birthed upon that typewriter in those early days of my self-imposed life sentence as a felonious hunt-and-pecker. I worked for the college paper, so there were news stories and personal columns aplenty. I was required to turn in material related to my meandering pursuit of a degree. I inclined toward fantasy fiction. If I ever actually finished anything in that genre, I cannot summon forth relatable details. Surely there were swords. And maybe some dragons.

Eventually, the grim reality of having to make a living dropped like a giant dog turd right into my lap. That much was not a fantasy. The Underwood stayed with me through what ended up being a two-year reporting stint with the El Paso Times. It came with me when I uprooted to Colorado, where I ended up living for 24 years. I used it while working for a series of newspapers and magazines, clear up to the point that the very first generation of personal computers appeared. When that happened, I placed the Underwood in its faux leather case and stored it in a closet, where it remained …

… until the past came a-callin’.

H — the ex-roommate who walked with me to the pawnshop when I first procured my Underwood in New Mexico — had fallen on hard times. Very coincidentally, our third roommate from our college days in Silver City — “B” — and his significant other “D” — were also living in Denver, where I holed up for a couple years trying in vain to carve out a career as a rent-paying freelance writer. We decided to move H up to Colorado. Help him find an apartment and land a job. Help him get back on his feet. Our intentions were good, but they were very poorly executed. We did not know that H had developed a problem with alcohol that was significant enough that he had spent time in a rehab facility. We treated his arrival in Colorado like one big frat party. Our adult beverage intake was purposefully out of control. H spiraled further downward, with our enthusiastic assistance. Would have been nice had he fessed up to his situation. Would have been nice had B, D and I paid better attention.

During that time, H borrowed my Underwood typewriter, which I considered to be a sign that he was perhaps working to overcome his precipitous drop by way of returning to his playwright roots. No such luck. Sadly, not long thereafter, H hit rock bottom with his drinking. His parents drove 15 hours to the Mile High City and carried him to his childhood home deep in one of the most remote and desolate parts of New Mexico. It did not dawn on me for some months that H had taken my Underwood typewriter with him.

I lost touch with both my Underwood and H.

Then, some years later, B and D, having relocated to a faraway city, contacted me and asked if I knew anything about an old Underwood typewriter they had unearthed under a pile of boxes in their garage. Turned out that H had not taken my Underwood with him down to the desert after all. He had left it behind. Apparently, he was inclined to push the delete button on his time in Denver.

B and D mailed my Underwood to me. I was giddy with excitement, having decided upon hearing the news of its resurrection, that it might be fun to occasionally reconnect to my earliest attempts to seriously butcher the English language. To again hear the tap-tap-tap that once drove me out of high school typing class.

Alas, that excitement was dashed when I, upon opening the package, saw that the typewriter had become a casualty of war. It had numerous bent parts and the frame was badly out of kilter. It had become a three-dimensional isosceles trapezoid. I took it to a typewriter repair outfit, where my Underwood was declared unfit for duty. It was, and remains, unusable.

So, for the past 20-plus years, it has been relegated to a station well beneath its one-time status: It is a decoration. A reminder.

I have no idea who owned my Underwood before it came my way via a pawn shop in southwest New Mexico. It would have been about 37 years old at that time. Given its model name, was it once the possession of a student who used it to write the same types of papers I toiled over while seeking a college diploma? It might have been owned and operated by a secretary whose fingers could fly over the QWERTY landscape with nary a bottle of Wite-Out or Liquid Paper brought to bear. Or, being portable, it might have been owned by a fellow journalist/writer, a foreign correspondent maybe. It’s possible my typewriter has visited more countries than I have! It might have produced Broadway plays and Pulitzer Prize winners before ending up in a pawn shop America’s Empty Quarter.

Did its previous owner upgrade? I mean, by 1977, electric typewriters were available.

Did someone die?

When it was handed over to the pawnbroker, did someone cry?

Was someone desperate for the money? (I have been that desperate.)

No matter. I had given it a useful second life, if for only a relatively short period, even if, at the end, it became crippled because, one day back in 1977, it entered the meandering flow of my existence.

Because it rests next to my desk, I look at my old Underwood often. I keep it well dusted. I occasionally make contact with the keys that first introduced me to the convoluted magic of QWERTY. And I try to remember what my then-20-year-old disheveled self was thinking as he tried to learn how to type and as he tried to learn how to write.

I didn’t realize at the time that what I was doing was pure, unadulterated stream-of-consciousness. Probably never heard the term, which, of course, can cover a lot of creative acreage. I placed my fingers on those keys and hoped for the best. I became a willing test subject for the infinite monkey theorem.

Now, all these years later, all these millions of published words later, I can scarcely face a keyboard without a well-delineated plan of attack. The spontaneity of my youth got waylaid by grown-up responsibilities. Most everything I now write has an end-game purpose: to make a living. To pay the mortgage. That was the plan all along, ever since I moved to the West with the goal of shedding my borderline-illiterate skin. But something got lost along the way. I miss that something.

I keep my wounded Underwood not merely in my house but close to my desk as a reminder that there’s nothing wrong with having no idea what you are doing, where you are going or how you’re going to get there. Keep on typing, even if you don’t know how. What could possibly go wrong?

END

Editor’s Note: M. John Fayhee’s latest book, A Long Tangent: Musings by an Old Man & His Young Dog Hiking Every Day for a Year” (Mimbres Press), ISBN 978-1-958870-08-2, paperback. It’s a good read. Take the ISBN to your local bookstore and order A Long Tangent. John will be appreciative.

If you would like to comment on John’s essay or just say hi, send a note to alanbearstark@gmail.com and I’ll pass the note along to John. Paid subscribers, please leave a comment by clicking on the button.

Mountain Passages doesn’t pay writers very well, but if you subscribe, I’ll share half of the money with John. However, a FREE subscription to Substack is available if you just click the button. When you get to the subscription page, go all the way to the right to sign-up for a free subscription. A paid subscription is always appreciated; I’m slowly writing my way to buying a gravel bike.

If you don’t like subscriptions but like this piece, buy me a cup of coffee by clicking the button below. John will get half, so splurge and buy two cups of coffee.

Don’t like commerce? Times are tough, so I get it. One of the ways I can build a Substack notebook is to add subscribers. Ask a friend to subscribe, please. In any event, thank you for reading Mountain Passages, an archive is available at alanstark1@substack.com

Luckily I took typing in high school. Served me well throughout my publishing career. I could hear those twenty five typewriters compete for 62 words a minute—no mistakes. The return of the carriage, the ring of the bell. I can see starting the day with that could lead to a psychological break. Another great read John.